Can Australia economically survive without China?

In 2009, China’s need for Australia‘s natural resources and agricultural exports made China an indispensable commercial partner.

In reality, in 2018-2019, Australia’s imports and exports totaled $235 billion from China, while they totaled just $137.4 billion from the Five Eyes allies.

Together, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and the United Kingdom make up the “Five Eyes” alliance.

About 38% of Australia’s total commerce with all countries in 2019 came from China. This makes severing ties with China in terms of trade all but impossible. Certainly, the quantity of resources exported from Australia to China is expected to increase. These numbers highlight Australia’s reliance on the Chinese economy.

Investments from Abroad in Australia

Foreign direct investment is crucial to Australia’s economy. With barely 4% of total FDI, China is merely the ninth largest investor in Australia. China’s pace of FDI exports is modest compared to that of industrialized nations (OFDI). Since 2000, when China launched its official ‘go global’ policy to promote its OFDI, the country has seen dramatic growth in its OFDI. China’s OFDI is expected to rise, and this expectation is supported by the data. When ranked, Hong Kong is sixth. Foreign direct investment (FDI) from China and Hong Kong is a force that cannot be disregarded.

There is a political indication of resistance to Chinese investment as of late. Because it was “contrary to the national interest,” Treasurer Josh Frydenberg called off a $600 million sale of the firm that produces Pura milk, Dare iced coffee, and Yoplait yogurt to a Chinese corporation. The Treasurer did not elaborate on his worries or explain how the pact would hurt Australia’s interests, though.

However, FDI is not a quick fix for Australia’s collapsing economy because to COVID-19. The June quarter GDP decrease of 7% and the March quarter GDP loss of 0.3% reported by the Bureau of Statistics means Australia’s economy has shrunk for two straight quarters. A recession has begun in Australia.

Dave Sharma has served as an ambassador to Israel, the head of the prime minister’s diplomatic team, and the chairman of the joint subcommittee on foreign affairs and assistance in the Australian parliament.

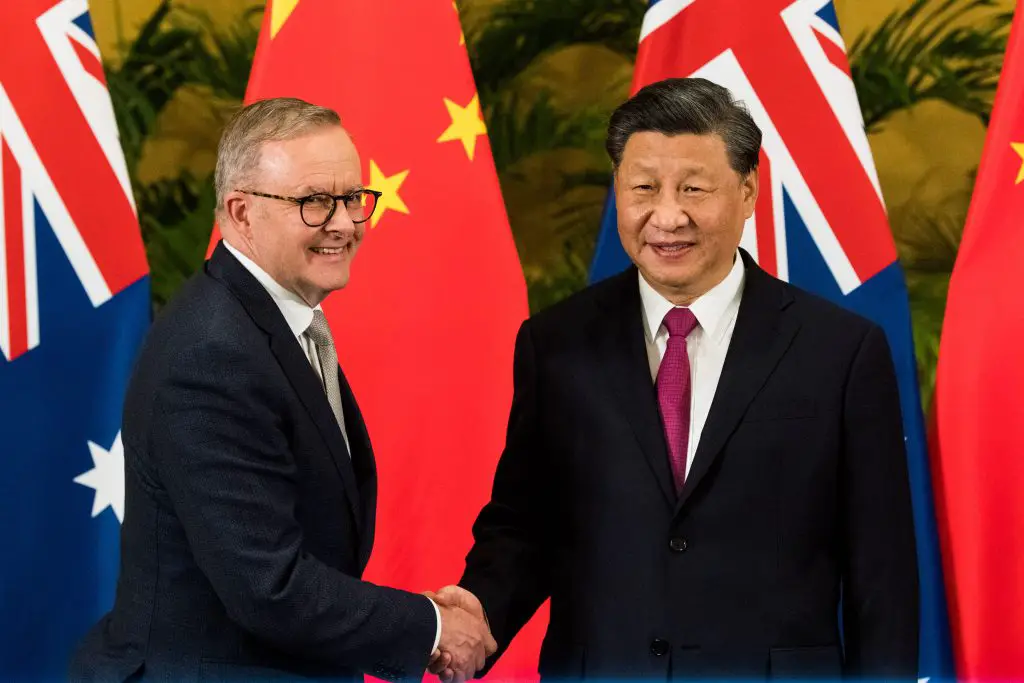

On the fringes of the G20 conference in Bali last week, Chinese President Xi Jinping met with Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese for the first time in almost six years.

Disconnecting from a bilateral agreement, prohibiting Huawei Technologies from Australia’s 5G networks, ramping up criticism of inbound investment portfolios, making legislation against foreign government influence, and leading calls for an independent inquiry into the origins of COVID-19 all contributed to Australia being placed in the diplomatic deep freeze by China.

In 2020–21, China slapped punitive tariffs on a variety of Australian goods, including wine, cattle, barley, lumber, lobster, and coal, marking a low point in the relationship. Diplomats from China’s embassy in Australia gave reporters an unusual list of 14 complaints they said needed to be resolved before bilateral ties could return to normal.

China wanted to punish Australia as a warning to other countries, but their efforts were fruitless.

The new center-left administration in Australia has made no effort to resolve the 14 concerns raised by Albanese before their meeting in Bali.

No changes have been made to China’s trade restrictions, but impacted industries have sought new outlets for their products. Overall exports to China remain robust, supported by commodities like coal, iron ore, and natural gas that Beijing cannot acquire elsewhere at reasonable prices. Australia no longer finds the absence of large numbers of Chinese students or visitors a problem.

We are seeing China change its methods, but not its overall policy. The core goals and red lines of China have not altered, and the dynamic of competitiveness and geopolitical rivalry between the United States and China will continue. There is no hope for a new age of international collaboration.

However, the contours of a new global equilibrium are becoming apparent, one with a lower degree of background tension and, thus, a reduced danger of mistake and possible escalation.